OSPO in China – The Institutional Journey of Open Source.

Thu Oct 30, 2025 | 2500 Words | 大约需要阅读 5 分钟 | 作者: 「开源之道」·适兕 && 「开源之道」·窄廊 |

以下内容由 Slides 开源项目办公室在本土,丢给 ChatGPT 所生成。

🗣 Speech: OSPO in China – The Institutional Journey of Open Source

- Speaker: Kuo Sì (适兕), The Way of Open Source

- Event: Open Source @ Siemens 2025

- Date: October 30–31, 2025

Opening & introduction myself

Good afternoon everyone, It’s a great honor to speak here at Siemens Open Source Day 2025. My name is kuo Sì, the author of The Way of Open Source, and for the last several years, I have been traveling across China to understand how companies, institutions, and governments are trying to adopt open source — and what happens when they do.

Today, my talk is titled “OSPO in China – The Institutional Journey of Open Source.”

I want to explore a question that goes far beyond software engineering:

What happens when a new institutional form — the Open Source Program Office — enters an ecosystem that has not yet internalized the culture, trust, and legal logic of open collaboration?

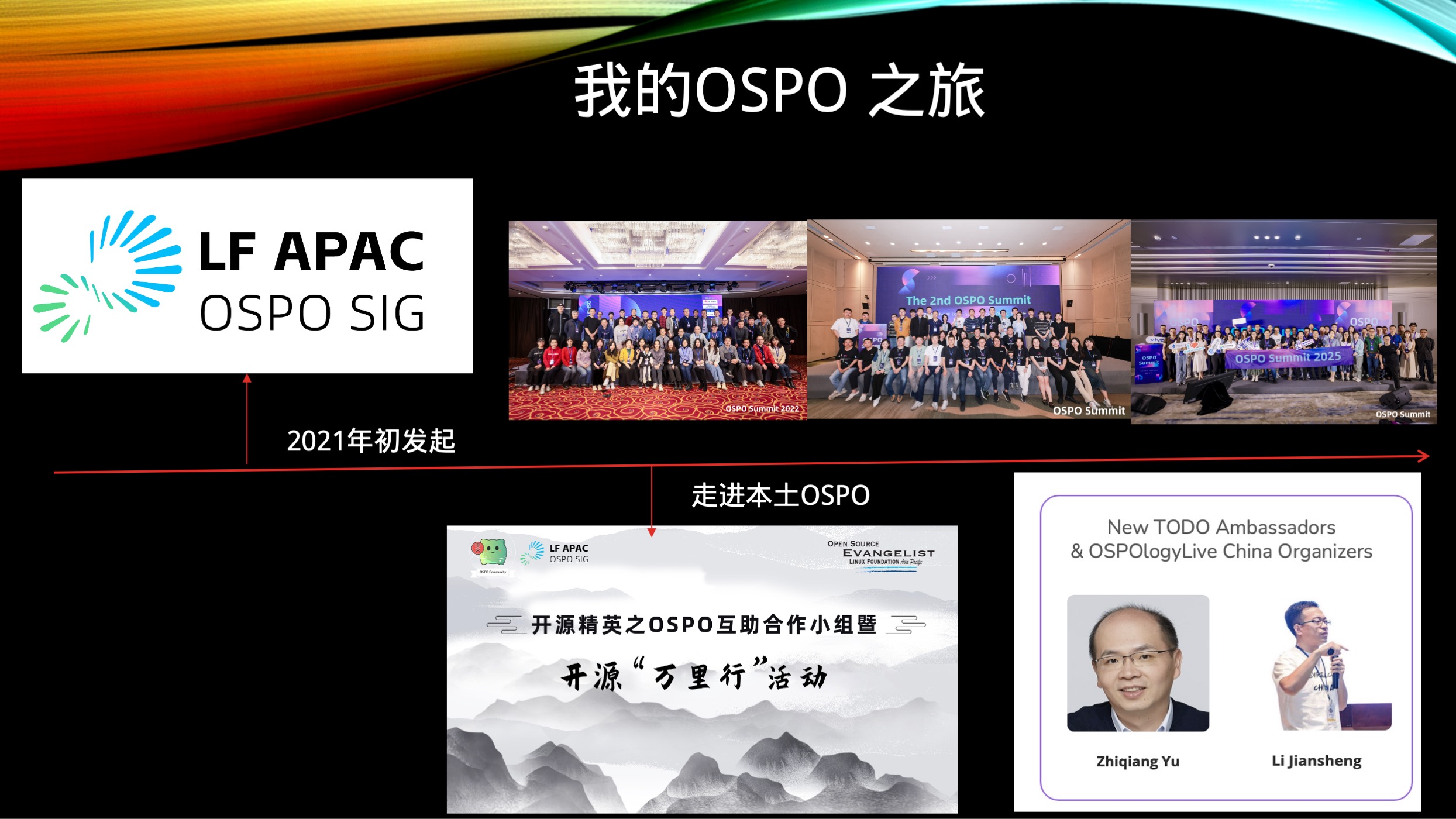

1. My OSPO Journey

I think I know OSPO in local, Because I did something in the past 5 years.

My journey with OSPOs started in early 2021. with Mr Yu , we found LFAPAC OSPO SIG ,and support TODO Group. We Go into companies which created OSPO.

and importly we organized OSPO Summit every year. this is the event for OSPOer – doing the job of open source in their org. we share, communcation, learning in this event. and try to reslove problem together.

and we host OSPOlive , the online knowledge share.

Tips

Back to 2021 , “OSPO” was an almost unknown term in China. Most companies had open source teams, legal advisors, or developer relations, but there was little understanding that OSPO is not about technology management — it is about institutional innovation.

2. Open Source as an Institutional Innovation

Let us start with a simple idea.

Companies are one of the greatest inventions of modern civilization. Open Source is another.

Both are ways of organizing human cooperation at scale — but their logics are fundamentally different.

Companies rely on hierarchy, contracts, and private property. Open Source relies on trust, transparency, and shared commons. They are two different operating systems for human collaboration.

The OSPO — the Open Source Program Office — is the bridge between these two worlds. It translates corporate structures into community logic, and community principles into corporate governance.

That is why I always say:

OSPOs are not technical managers — they are institutional translators.

They rebuild compatibility between the compliance mechanisms of the company and the trust mechanisms of the open source ecosystem.

3. A Framework for Understanding:

Learning, Internalization, Transformation

When we analyze OSPOs in China, we can see a clear pattern of institutional diffusion:

Learning and Imitation Companies learn from global practices — from Google, Red Hat, Microsoft, or the TODO Group.

Internalization and Practice Around 2021, some Chinese companies began to formally acknowledge OSPOs. They tried to embed them into existing departments — often under technical committees, ecosystem teams, or legal offices.

Transformation and Mutation But once the idea enters a new institutional environment, it starts to mutate. Some OSPOs became marketing arms. Some became compliance checklists. Some were reduced to administrative sub-departments. Others simply disappeared.

This process is not unique to China — but it is more visible here because of the non-endogenous nature of institutional change: The OSPO is imported, not organically grown.

4. Mapping the Landscape

According to the TODO Group landscape and reports from LF APAC and the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT), we now see OSPO-like structures across industry, education, and government sectors.

There are OSPOs in major internet companies, in universities, and even in ministries. However, the functionality and autonomy of these OSPOs vary drastically.

Some are genuine attempts at cross-boundary governance. Others exist only for public relations — as one executive once told me:

“We have an OSPO because it looks modern.”

5. Learning and Importing: The Global Wave

Globally, the OSPO concept emerged at the end of the 1990s and matured through the success of Google, Microsoft, and Red Hat. It became a visible, codified model through communities like the TODO Group.

Between 2017 and 2019, the Linux Foundation and GitHub published their OSPO guides, making “best practices” visible and transferable.

In essence, the OSPO movement is the institutionalization of open collaboration — a recognition that open source is not chaos, but a new form of organized production.

Chinese companies, seeing this, began to imitate the visible layer — creating OSPOs by name, copying policies and governance templates — but the invisible layer of trust, autonomy, and shared values was much harder to transplant.

6. Internalization: Practice within Hierarchy

Most Chinese companies placed their OSPOs under existing power structures:

- Under technical committees (but with little actual power),

- Under ecosystem or marketing teams (for external communication),

- Or under legal departments (for risk control).

Why? Because in a vertically managed organization, any horizontal mechanism is seen as an anomaly. The OSPO’s cross-departmental nature clashes with the company’s hierarchical DNA.

As a result, OSPOs often end up being ceremonial institutions — They exist in the organizational chart but not in daily governance.

7. Transformation: Mutation and Symbolism

As institutional sociologists Meyer and Rowan once said,

“Organizations adopt formal structures to gain legitimacy, not necessarily efficiency.”

In China, this is exactly what happened. The OSPO became a symbol of modernity — a sign that “we understand open source.”

Yet in practice:

- Some OSPOs became marketing exits, broadcasting success stories.

- Some mixed up Inner Source with open collaboration.

- Some were empty shells, existing only for annual reports.

- Some turned into tools for rent-seeking within bureaucracy.

- Only a handful truly functioned as bridges between community and enterprise.

8. The Ideal Vision of an OSPO

In an ideal world, an OSPO can achieve:

- Mutual growth between the organization and the community.

- Sustainable governance of the commons.

- A foundation for the next generation of innovation and economic growth.

- Empowerment of employees and contributors alike.

- A leap beyond traditional production models — as Linux, Android, and Kubernetes already demonstrate.

In short, an OSPO should be a living institution of trust, not a department for publicity or compliance.

9. Why the Gap?

Why is there such a large gap between the ideal OSPO and the actual OSPOs in China?

Because many organizations view open source as a technological artifact, not an institutional revolution. They see it as consumption, not construction.

They don’t understand the legal and cultural meaning of GPL. They don’t believe in self-organized governance. They lack the mindset of building commons — and above all, they lack a modern institutional foundation capable of supporting distributed trust.

In short:

The problem is not that OSPOs don’t work in China. The problem is that the organizations hosting them are not yet ready for open institutions.

10. Deeper Reflection: Institutions and Modernity

Jason Potts, in Innovation Commons, wrote:

“We invent institutions to govern cooperation.”

This sentence is simple but profound. It reminds us that innovation is not only technological — it is institutional. Without the right institutions, technologies decay into propaganda or control.

The OSPO is one such invention. It is a test of whether a society or a company can build cooperation beyond command, trust beyond control, and innovation beyond hierarchy.

The story of OSPOs in China is not just a story about software. It is a story about modernization, trust, and institutional courage.

Every OSPO is a small act of defiance — a declaration that collaboration can exist even in hierarchical systems. It might be imperfect, fragile, even symbolic — but it is the seed of a different future.

So let us continue to build, translate, and nurture these institutions — not as decorations of modernity, but as living systems of cooperation.

Because, as Jason Potts reminded us,

We invent institutions to govern cooperation.

And the OSPO, in its truest sense, is one of the most human inventions of our digital age.

Thank you and enjoy the next seesion.

以下内容和演讲无关~

11. The Chinese Context: Institutional Inertia

Let me speak frankly.

In China, institutional learning is often mimetic rather than transformative. When we import a foreign model, we tend to preserve our old logic inside it. This is what I call “institutional inertia.”

It’s like wearing a modern suit while keeping feudal habits. We borrow the form of modernity, but not its logic.

So when a company or a government “embraces open source,” it does so through the lens of control. It doesn’t open up — it absorbs. It doesn’t share — it redefines ownership. It doesn’t build trust — it simulates it.

12. Institutional Colonization:

How Old Systems Invade New Ideas

When an old system encounters a new institution, three reactions occur:

Defensive Absorption The old system “accepts” the new form to protect itself. Example: creating a “national open source foundation” — not to empower communities, but to monitor them.

Semantic Reversal The language of openness is preserved, but meanings are reversed. “Open collaboration” becomes “controlled participation.” “Transparency” becomes “auditing.” “Community” becomes “administration.”

Legitimacy Capture The institution is used to gain moral or political legitimacy — “We are open too.” This is not adoption; it’s colonization.

13. Economic Theory Perspective – Post-Catch-Up Trap

Economist Xiaokai Yang once wrote about the post-catch-up disadvantage. He argued that developing economies can easily copy technologies, but not the institutions that make those technologies flourish.

That’s exactly what we see in the open source field. China’s companies can reproduce any software stack, but they struggle to internalize the trust, transparency, and reciprocity that define open source governance.

You can imitate Linux’s code, but not the social contract that sustains it.

14. The Role of OSPOs in This Landscape

Seen from this angle, OSPOs in China are not failures — they are symptoms of a deeper transformation.

They reveal the boundaries of our current institutional capacity. They tell us how far our organizations can go — and where they must change.

In a way, each OSPO is like a small experiment in institutional evolution: some mutate, some die, a few adapt.

And that is precisely why studying OSPOs matters — because they reflect not just corporate governance, but the civilization’s ability to reinvent cooperation itself.

15. Looking Forward: Building the Soil, Not the Mirror

If I may summarize this entire journey in one metaphor:

OSPOs are like puddles of water on the ground — reflecting the sky of openness, yet rooted in the soil of our institutions.

If the soil remains hard and dry, the puddle soon evaporates. If we want the reflection to last, we must change the soil — not just admire the sky.

That means:

- Empowering OSPOs with real authority,

- Building legal and cultural understanding of open source licenses,

- Encouraging community governance within companies,

- And most importantly, cultivating trust as infrastructure.

关于作者

「开源之道」·适兕

「发现开源三部曲」(《开源之迷》,《开源之道》《开源之思》。)、《开源之史》作者,「开源之道:致力于开源相关思想、知识和价值的探究、推动」主创,Linux基金会亚太区开源布道者,TODO Ambassadors & OSPOlogyLive China Organizer,云计算开源产业联盟OSCAR(中国信息通信研究院发起)个人开源专家,OSPO Group 联合发起人。

「发现开源三部曲」(《开源之迷》,《开源之道》《开源之思》。)、《开源之史》作者,「开源之道:致力于开源相关思想、知识和价值的探究、推动」主创,Linux基金会亚太区开源布道者,TODO Ambassadors & OSPOlogyLive China Organizer,云计算开源产业联盟OSCAR(中国信息通信研究院发起)个人开源专家,OSPO Group 联合发起人。

「开源之道」·窄廊

来自于大语言模型的 Chat,如DeepSeek R1、Google Gemini、ChatGPT 、Kimi、甚至整合类应用 Monica等, 「开源之道」·窄廊 负责对话、提出问题、对回答进行反馈等操作。

来自于大语言模型的 Chat,如DeepSeek R1、Google Gemini、ChatGPT 、Kimi、甚至整合类应用 Monica等, 「开源之道」·窄廊 负责对话、提出问题、对回答进行反馈等操作。